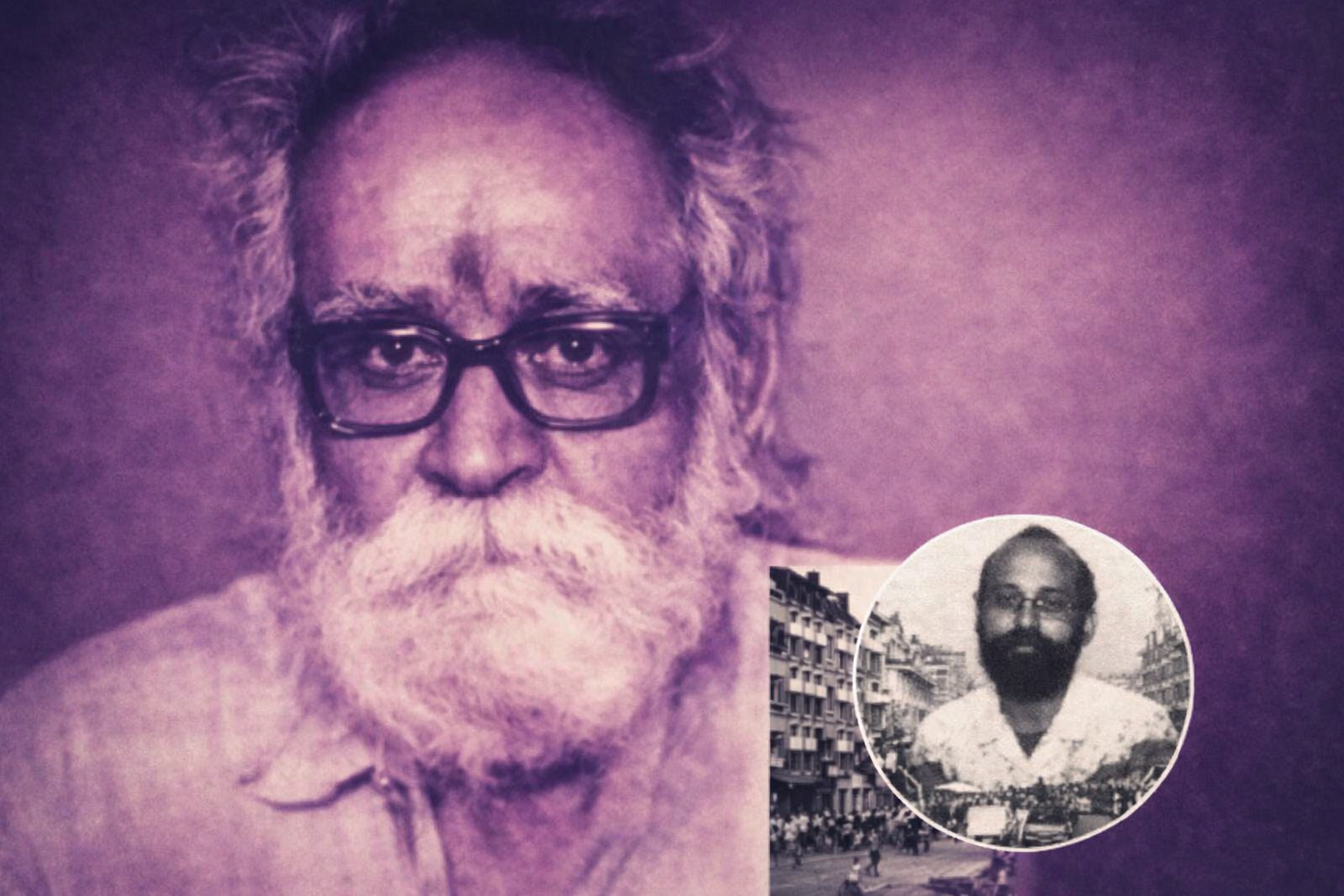

The Forgotten Saviour

The Statesman

I. Core Theme of the Article

The article revisits the life and legacy of Gopal Chandra Mukherjee, often called the “Lion of Bowbazar”, who organised armed resistance against communal violence during the Direct Action Day riots of 1946 in Calcutta.

It situates him within:

- The communal turmoil preceding Partition

- Hindu-Muslim violence in Bengal

- The moral dilemma of self-defence versus vigilantism

The article attempts to restore him to public memory as a defender of vulnerable communities.

II. Key Arguments Presented

1. Context of Direct Action Day and State Collapse

The article argues that:

- The Great Calcutta Killings represented a breakdown of state authority

- Police and administration failed to protect civilians

- Ordinary citizens were left to fend for themselves

In this vacuum, Mukherjee emerged as an organiser of resistance.

2. Self-Defence vs Vigilantism

A central moral question raised:

When the state fails to protect citizens, what are the ethical boundaries of self-defence?

The article suggests that Mukherjee’s actions were framed as:

- Defensive

- Protective

- Community-oriented

Rather than expansionist or retaliatory.

3. Historical Erasure and Selective Memory

The piece argues that:

- Partition narratives often focus on elite negotiations

- Grassroots defenders and local actors are forgotten

- Certain historical figures are omitted due to ideological discomfort

Thus, Mukherjee is portrayed as a neglected figure in mainstream historiography.

4. Moral Complexity of Violence

The article does not romanticise violence outright.

Instead, it frames Mukherjee’s role within tragic circumstances.

It raises the question:

Can organised armed resistance ever be morally justified in communal breakdown?

III. Author’s Stance

The author adopts a rehabilitative stance toward Mukherjee.

Tone:

- Sympathetic

- Revisionist

- Contextual rather than celebratory

The narrative positions him as:

- A protector during chaos

- A symbol of community self-organisation

- A morally complex but necessary actor

The stance challenges one-dimensional depictions of pre-Partition violence.

IV. Possible Biases and Limitations

1. Risk of Heroification

While contextualised, the narrative may:

- Risk normalising retaliatory violence

- Underplay excesses committed by armed civilian groups

- Blur lines between self-defence and escalation

The danger lies in retrospective moral endorsement.

2. Limited Muslim Perspective

The account foregrounds Hindu vulnerability but does not equally explore:

- Muslim casualties

- Reciprocal narratives

- Multi-sided communal suffering

Partition violence was symmetrical in brutality across regions.

3. State Accountability Underexplored

The larger structural failure of:

- Colonial governance

- Communal mobilisation politics

- League–Congress breakdown

Could have been more deeply analysed.

V. Pros and Cons of the Argument

Pros

• Brings neglected historical figures into discourse

• Raises ethical questions about state failure

• Encourages nuanced understanding of Partition-era violence

• Challenges simplistic binaries of aggressor/victim

Cons

• Risks legitimising armed communal mobilisation

• May be appropriated for contemporary political narratives

• Insufficient emphasis on rule-of-law primacy

• Could oversimplify complex communal causation

VI. Policy and Contemporary Relevance

Though historical, the article carries modern implications.

1. State Capacity and Law & Order

When the state fails to protect:

- Vigilantism emerges

- Communal polarisation intensifies

- Trust in institutions collapses

Lesson: Institutional robustness prevents moral ambiguity.

2. Historical Narratives and Identity Politics

Selective memory shapes:

- Communal identity

- Political mobilisation

- Public discourse

Responsible historiography must avoid instrumentalisation.

3. Boundaries of Self-Defence

In constitutional democracy:

- Monopoly of violence rests with the state

- Self-defence cannot become organised paramilitary mobilisation

The article invites reflection on this boundary.

VII. UPSC Relevance

GS Paper I

• Modern Indian history – Partition and communal politics

• Role of local actors in freedom movement

• Social consequences of communal violence

GS Paper II

• Law and order as state subject

• Role of state in protecting citizens

• Constitutional morality

GS Paper IV (Ethics)

• Moral dilemmas in crisis situations

• Justification of violence in extreme contexts

• Individual conscience vs institutional authority

VIII. Balanced Conclusion and Future Perspective

The article succeeds in complicating historical memory.

It reminds us that during moments of institutional collapse, individuals may step into morally ambiguous roles.

However, democratic societies cannot derive legitimacy from vigilantism, even when born of fear and survival.

The enduring lesson is not the celebration of armed self-defence.

It is the imperative of building institutions so strong that citizens never feel compelled to take the law into their own hands.

History must illuminate complexity — but it must also reinforce the primacy of constitutional order over communal retaliation.

In remembering forgotten saviours, we must also remember the cost of a state that fails.