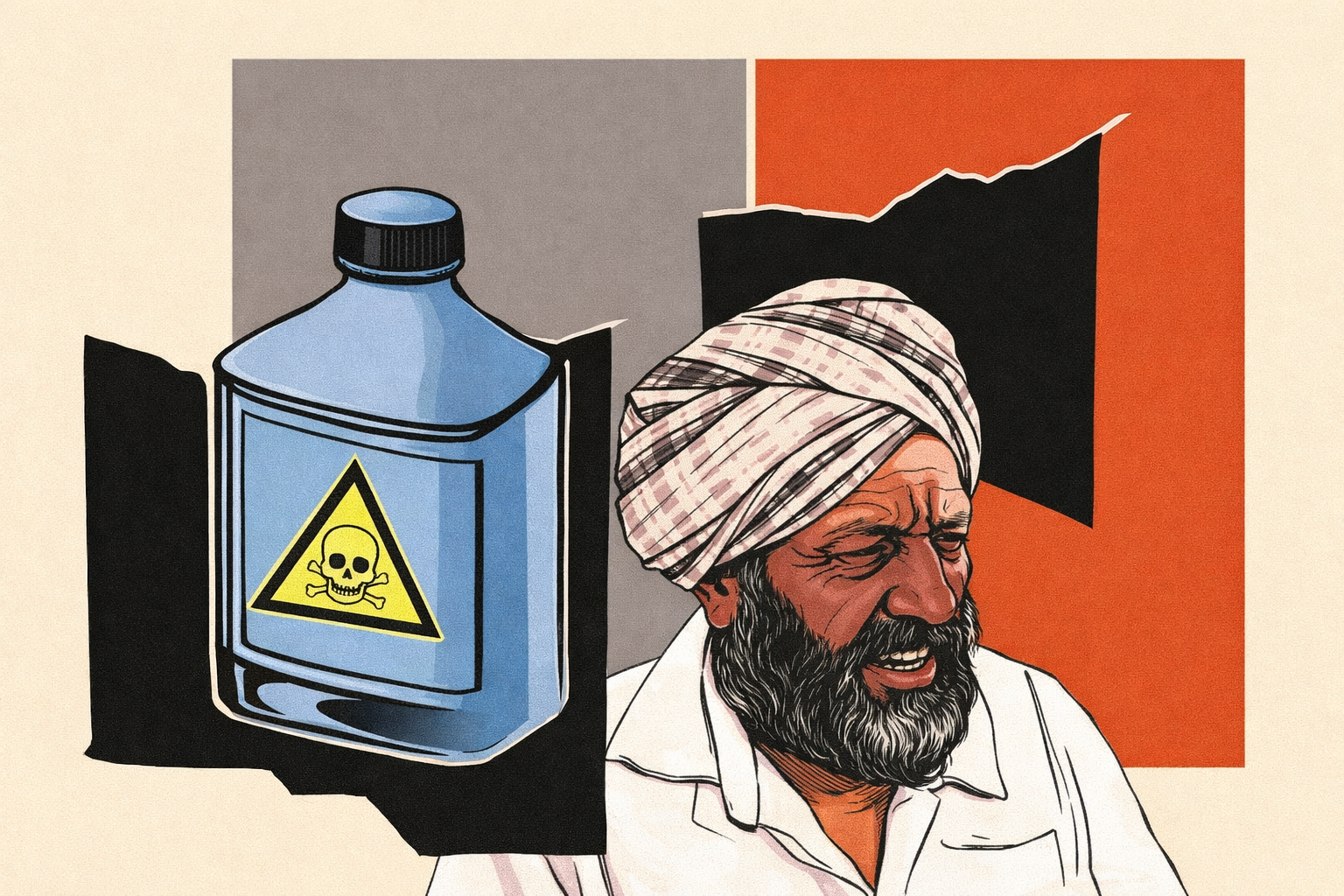

How lobbying undermines public health

The Tribune

I. Central Thesis and Core Argument

The article argues that corporate lobbying systematically weakens public health regulation by distorting scientific evidence, influencing regulatory institutions, and delaying or diluting policy action. It contends that when commercial interests shape health policy, regulatory capture replaces evidence-based governance, leading to long-term harm to populations rather than immediate, visible crises.

The core claim is that public health failures are often not due to lack of scientific knowledge, but due to deliberate political and economic interference, where lobbying exploits uncertainty, legal complexity, and institutional inertia.

II. Key Arguments Presented

1. Power Asymmetry Between Corporations and Citizens

The article highlights how individuals and communities lack the financial, legal, and institutional capacity to challenge large corporations, whereas industry actors can deploy sustained lobbying, litigation, and public relations strategies.

2. Manipulation of Scientific Evidence

Corporate-sponsored studies, selective data disclosure, and regulatory submissions are shown to influence safety assessments, creating doubt where scientific consensus exists.

3. Regulatory Capture of Institutions

Agencies tasked with protecting public health are portrayed as vulnerable to pressure from industry through revolving doors, lobbying access, and political influence.

4. Delayed Policy Action as a Strategy

Even when harm is acknowledged, lobbying often succeeds in postponing bans, restrictions, or safety norms—prolonging exposure and damage.

5. Global Replication of the Pattern

The article situates the issue beyond one country, arguing that the same lobbying playbook operates across jurisdictions, particularly in chemicals, agriculture, pharmaceuticals, and food systems.

III. Author’s Stance

The author adopts a strongly critical, public-interest-oriented stance, clearly siding with precautionary regulation and scientific independence. The tone reflects concern over democratic accountability, arguing that health governance has been subordinated to profit-driven logic.

The article positions lobbying not as neutral advocacy but as a structural threat to public welfare, demanding regulatory vigilance rather than accommodation.

IV. Implicit Biases and Framing

1. Normative Bias Against Corporate Influence

The article assumes lobbying is predominantly harmful, with limited acknowledgement of legitimate industry participation in policymaking.

2. Emphasis on Structural Failure Over Administrative Capacity

While corporate influence is scrutinised, internal weaknesses of regulatory institutions—such as underfunding or skill deficits—are less examined.

3. Limited Discussion of Countervailing Safeguards

Judicial review, civil society activism, and international standards receive less attention as corrective mechanisms.

V. Strengths of the Article

1. Clear Causal Linkage

The article convincingly connects lobbying → regulatory delay → prolonged exposure → public health harm.

2. Science–Policy Interface Explained Well

It demystifies how scientific uncertainty can be politically manufactured and exploited.

3. Ethical Governance Lens

Frames public health as a moral and constitutional obligation, not a negotiable economic variable.

4. High UPSC Relevance

Directly links to GS-II (governance, accountability), GS-III (health, regulation), and GS-IV (ethics in public policy).

5. Long-Term Perspective

Shows how flawed regulatory decisions can shape health outcomes for decades.

VI. Limitations and Gaps

1. Lack of Policy Design Detail

While diagnosis is strong, concrete regulatory design solutions are not elaborated in depth.

2. Binary Framing of Stakeholders

Industry is largely portrayed as adversarial, with little nuance regarding collaborative regulatory models.

3. Insufficient Focus on Developing Countries

The analysis could have more explicitly examined how lobbying affects weaker regulatory regimes.

VII. Policy Implications (UPSC GS Alignment)

GS Paper II – Governance and Accountability

• Highlights risks of regulatory capture

• Reinforces need for institutional autonomy and transparency

• Raises questions of democratic deficit in policymaking

GS Paper III – Public Health and Regulation

• Underlines importance of precautionary principle

• Shows how weak regulation amplifies non-communicable disease burden

• Emphasises role of state in risk mitigation

GS Paper IV – Ethics in Public Administration

• Conflict of interest

• Integrity of scientific advice

• Public trust versus private profit

VIII. Real-World Impact Assessment

Public Health Outcomes

• Continued exposure to harmful substances

• Rise in chronic diseases and healthcare costs

• Disproportionate impact on vulnerable communities

Governance Outcomes

• Erosion of trust in regulators and science

• Judicialisation of health policy

• Policy paralysis despite evidence

Economic Outcomes

• Short-term industry gains versus long-term societal costs

• Increased public expenditure on healthcare and remediation

IX. Balanced Conclusion

The article makes a compelling case that lobbying, when unchecked, corrodes the foundations of public health governance. By demonstrating how distorted science enters the policy record and shapes law for decades, it underscores that health regulation is as much a political challenge as a technical one.

However, a more balanced exploration of regulatory reform mechanisms and institutional resilience would have strengthened the analysis. Effective governance requires not only exposing undue influence but also designing systems that can withstand it.

X. Future Perspectives

• Strengthen conflict-of-interest norms in regulatory bodies

• Institutionalise independent, publicly funded scientific research

• Mandate transparency in lobbying and regulatory submissions

• Adopt precautionary approaches where evidence of harm exists

• Empower civil society and judicial oversight in health governance

Ultimately, the article reinforces a core UPSC-relevant insight: public health fails not because science is absent, but because power is unequally distributed. The task of governance is to realign policy with evidence, ethics, and the public good.